A lot can change in 30 years.

AK: The biggest thing is that WOTRians have changed their approach. When we were just doing watershed development, our work was centred around human beings. But slowly, as we kept learning, we started to realise that our work is also to restore the local ecosystem.

The Watershed Organisation Trust, called WOTR for short, started out back in 1993 to help villagers in drought-prone areas of Maharashtra prevent soil erosion and access water for their livelihoods. Now, three decades later, the organisation’s main focus is Ecosystem-based Adaptation – essentially, restoring ecosystems to help communities deal with the impacts of climate change.

That’s a pretty big shift from being focused primarily on people, to actually starting to see people as just one part of a much larger picture. So how did that come to be?

MD: Well, that’s a real story also.

Welcome to In Our Nature, a podcast by the ECOBARI Collaborative that uncovers what we need to do to protect ecosystems, so that they can protect us. I’m your host, Isha, and in this series, we explore our deep connections with the natural world, and how restoring nature can help us adapt to climate change. ECOBARI is a shared initiative of nine founding partners, and is convened by the Watershed Organisation Trust.

Our sixth and final episode in this series is about WOTR itself – in particular, about how and why the idea of Ecosystem-based Adaptation took hold within the organisation.

MD: The first time I went to a village to talk to the people about watershed development, I recall a woman lifting up her child, and she says, “how do I feed my child?”

Marcella D’Souza is the Director of WOTR’s research vertical, the WOTR Centre for Resilience Studies, or W-CReS; and she’s been a part of WOTR since its early days. She started her career as an allopathic doctor, but during a posting in rural Maharashtra, realised that people didn’t even have the basics – clean water and enough food to eat.

MD: My keen interest on addressing nutrition and giving them clean water so that they wouldn’t have to suffer from intestinal infections, which was very common, that fitted very well into the whole perspective of watershed development.

Marcella says that she wanted to address the core problem at hand, rather than prescribing medication as a band-aid solution. And it seemed like water was the key constraint.

MD: When I would travel to the villages during the monsoon season, there would be floods. We would be stuck on either side of the river, you know, because it was flooded, and we would be stuck for hours. But come the summer season, there was no water in the villages. So it was always a question of, what’s happening to the water? You’re getting good rains, but you don’t have water.

So access to water, through watershed development, was really the starting point.

MD: WOTR started out with the Indo-German Watershed Program. For the first 10 years, they contributed a lot to this cause.

Abhijeet Kavthekar, the regional manager for WOTR’s work in Dharashiv, an aspirational district in Maharashtra, has been a part of the team for the last 22 years.

MD: There is a liveness in this work with the community. [2:25] And the most important thing I found out is that I enjoy doing work that challenges me.

Abhijeet joined just as WOTR was going through something of an internal shift.

MD: I look at that period of 2000 to 2003 as a crisis year. And I’m calling crisis as a turning point.

And a big part of that crisis was something that the team, at the time, couldn’t fully understand.

MD: One of the big indicators for us whether our work in watershed development was really addressing the need was, is there distress migration? Because watershed development was improving soil conservation and water availability. So people should have water available for the second crop at least, and therefore they should not go on distress migration, or less. However, in the year 2002 or so, we started seeing distress migration.

Marcella correlated this with changes in the weather patterns.

MD: We found the year 2000, 2001, 2002, and 2003 we had four consecutive years of drought and drought-like conditions. [11:37] That was the time we said, something is not right. The area is used to having a drought year every three to four years. That was the norm. But four consecutive years of drought and drought-like conditions, supplying the whole district of Ahmednagar in tankers almost for this entire period, not normal.

So they started talking to partners abroad, in Switzerland, to understand what was going on.

MD: Then we started hearing about climate change, or rather, weather variability. We called it weather variability.

As Marcella said right at the start, watershed development was dependent on conserving water that was falling freely from the sky. But what happens to the program when the rain itself becomes unreliable?

AK: In the newspapers, we were reading about how climate change is discussed in the global context. But what kinds of impacts and risks would rural areas face, what kind of adaptation measures were possible, I didn’t have that kind of thinking in my mind at the time.

Abhijeet says that back then, they had a general sense of what climate change was – but they couldn’t easily correlate it to people’s experiences on the ground.

AK: At the global level, people were talking about the greenhouse effect, fossil fuels, those kinds of things. But in villages, people were experiencing soil erosion, water [shortages], crop losses, and increasing pest attacks. So people in the villages were experiencing this already, but what was causing it and what terminology was used to talk about it, there was a gap there.

The concept was new to everyone, but people were already experiencing it. So it took some time to be able to get through to people about it.

AK: At first, people felt like they already knew whatever we were trying to tell them, but when we started to talk to them about root causes and predictive risks, they started to take it more seriously.

To be able to take better action on those predictive risks, the team needed data.

MD: We put up the first automated weather stations in three villages. The first agenda was, you know, to get the people to have these automated weather stations in the village and be protected by the people. I have to say, they lived up to our expectation and beyond. Even the children would tell other children of other villages, don’t touch it. This is what it does.

And people could use that data to make decisions about how to change their cropping patterns or look after their animals under changing weather conditions – in other words, they could adapt.

AK: I’d like to give an example. In [a village called] Varudi Pathar, we set up an agromet station. So the concept of an agromet station was that people would find out what local weather conditions were, and could do their crop management accordingly. But the poultry farmers of that village would always come [to the agromet stations] to check the temperature. You also probably know that there is a particular temperature range that’s necessary for the regular growth of the birds. So [the poultry farmers] didn’t focus much on rainfall or wind speed. That’s when I realised that people use the technologies we are promoting to ensure that their livelihoods are sustainable – and they are thinking about it this way as well. So ultimately, the work we are doing is increasing their resilience.

This pilot in three villages eventually grew out into a full-fledged program on climate change adaptation, or CCA, supported by NABARD – which is the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development – and the Swiss Development Cooperation. This program included watershed development, climate smart agriculture, disaster risk reduction, clean energy, weather-based crop advisories, and more.

MD: But incidentally, it was not just addressing climate change. We also realised the value of doing the conservation of biodiversity, and we had the biodiversity registers. We did a lot of tools. We prepared the People’s Biodiversity Register, prepared at that time and endorsed by the state government.

Marcella mentioned People’s Biodiversity Registers, an initiative by the Indian government to help communities catalogue biodiversity in their area. WOTR worked with local people to prepare these registers, to raise awareness about the need to protect their ecosystems.

AK: At the time, we tried to implement climate-resilient agriculture on a large scale. Alongside that, we also focused on why preserving local biodiversity is important for us. We focused on different aspects within biodiversity – agricultural diversity, bird diversity, forest diversity – with the intent that if we could sensitise people, we would be able to mobilise them towards ecosystem restoration. [We told them that] in the next 10-15 years, if you conserve [the natural resources] that you have right now, that will really help protect you against losses from climate change. [29:23] And the great thing was that people started to open up and share their indigenous knowledge with us.

And the program turned out to be pretty successful. In fact, it was recently selected as one of 10 global case studies in the flagship Drought report by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, or UNCCD.

MD: And of the 10 case studies globally that were selected, WOTR’s project was selected from the Indian case study. Our case study that was implemented in the climate change adaptation project. We could bring out evidence of the economic returns, which was 3.5 – 3.9 times more in the villages which were treated as compared to villages that were not treated.

Despite rising climate stress, the villages that participated in the CCA project are economically better off than the villages that didn’t. So it worked!

Abhijeet attributes the success of the program to the diversity of stakeholders that were involved.

AK: When we started the work on climate change adaptation, it had three layers. [Climate] experts would put their opinions forward, implementers would look at it from their own perspective, and villagers were telling us what they thought should and shouldn’t happen. So ultimately, I feel that WOTR has been successful because all three categories of people contributed equally to the roadmap we created.

So four years of successive drought spurred a change in the organisation’s thinking, and made climate adaptation a priority. But where did this thinking around biodiversity come from?

It isn’t as straightforward as it may seem.

In the first decade of watershed development, WOTR planted trees to recharge groundwater. But in the turning point that Marcella spoke about, in the early 2000s, questions started to arise.

MD: We were reforesting the degraded forest lands, but we had a big issue to address. The farmers would set out their cattle to go and graze the land, and with that, the trees that were planted would be grazed. But in addressing that issue, we decided to grow saplings of trees that were not native to the area. And later on, we said, oh, we should have done it differently, because we need to be more aligned with nature, because the ecology of the forest has its own role within the ecosystem and the soil health, which we didn’t consider at that time. We looked only from the perspective of soil conservation, water conservation, which was fundamental. That helped us to bridge the gap with the people. But later on, once that was there, we said, we should have done it better.

There were a lot of questions – about which kinds of trees should be planted, and where.

MD: When we looked at the land classification that came down historically, there was a lot of land that was classified as unculturable wasteland. So we said, okay, this is unculturable wasteland. Let’s at least put trees so that the trees could force the water underground. When we look back, we said those were the grasslands that we have converted into tree cover. Now we are relearning, and we are going to explore areas to see how we can restore grasslands wherever possible. So that’s why we learned that we have to be willing to explore and not be afraid to say that we’ve made a mistake.

This realisation would lead to a paradigm shift within the organisation – and it was something that every member of the team had to reckon with.

AK: The biggest thing is that WOTRians have changed their approach. When we were just doing watershed development, our work was centred around human beings. We need water for them, farming for them, animals for them. But slowly, as we kept learning, we started to realise that our work is also to restore the local ecosystem. Like if we’re planting trees, we are also working on regenerating the forest ecosystem. So as an implementer, I would say the biggest thing is that this project gave me the opportunity to change my lens, for the first time.

MD: We were very clear that while we were doing watershed development at the time when we began, we were addressing the resource use. How do we use the soil? I’m using it very crudely, but I’ll still use the word ‘use’. And we were looking at water use, and we knew we had to manage water. But then going beyond it, we gradually, in the process, realised we are also a part of nature. So we don’t use nature only from an anthropogenic perspective, but the Anthropocene is a part of nature, which we have forgotten.

At the core of this realisation was recognising that every place is unique, with its own ecological niche, and needs to be treated differently.

MD: You have the climate layer. We looked at rainfall, we didn’t realise temperature, which we consider now. You look at the topography, you look at the soil quality, you look at the soil health. [24:00] You look at the hydrology, you look at the geology, which is very different from the hydrology. And over that, you have people who are surviving, and different types of people who are surviving, and different cultures of the people. How do you bring this all together? Understanding this and the uniqueness made us realise we still needed and still have a lot to learn. That’s what triggered us to start off our research unit.

Fast forward to 2019. W-CReS, WOTR’s research vertical, is up and running; and they’ve just been invited by a German think-tank called TMG to collaborate on a project.

MD: We were not clear about the Ecosystem-based Adaptation perspective. We called it climate change adaptation with biodiversity being an important component. But around early 2019 we were approached by TMG research, a German Institute, who was exploring organisations that were working on Ecosystem-based Adaptation. And when they spoke to us, we said, hey, this is exactly what we were looking for.

Marcella recalls that around the same time, WOTR was undergoing a rebranding exercise and running into roadblocks.

MD: When this agency was discussing our brand, we talked about land restoration, we talked about agriculture, we talked about water, we talked about people, we talked about climate change, and they said you can’t do everything. You have to decide whether you want to focus on water or you want to focus on agriculture. And we said, we can’t do water without doing the landscape, and we can’t manage water without people having good agriculture productivity, and we can’t do agriculture productivity without this. And we said, this has to be together.

But through their work with TMG, they realised there was a way to bring it all together.

MD: Suddenly these isolated – I’m calling them activities – of agriculture and water and land management, suddenly they had a convergence in this name called Ecosystem-based Adaptation.

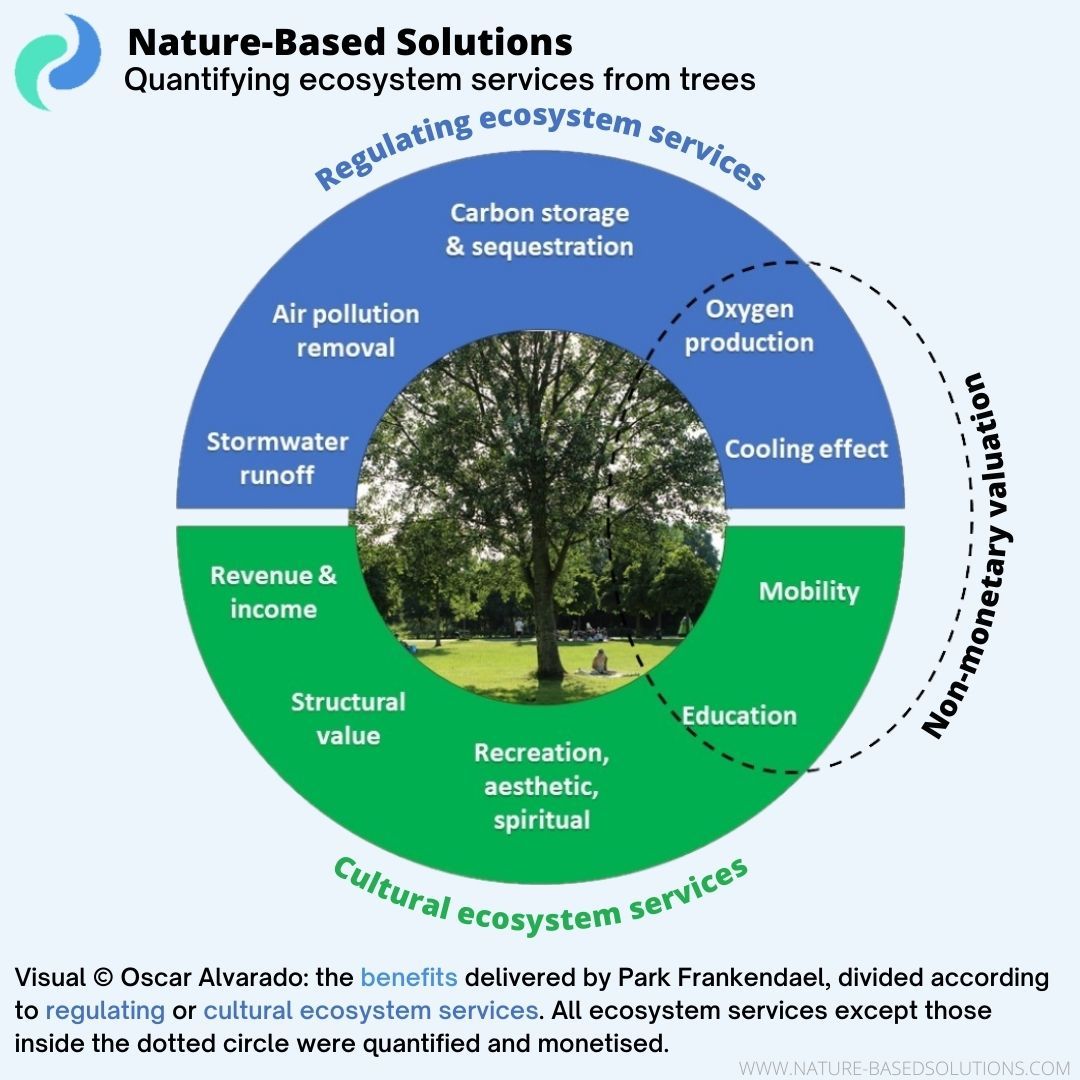

Ecosystem-based Adaptation, or EbA, became the umbrella term that could fit this entire spectrum within its three pillars.

MD: So the three pillars are – the first one is strengthening the different aspects of the ecosystem. The land, the water, the biodiversity, and nature all around there. The second pillar is on climate change adaptation, helping the community to be able to adapt to climate change. Also to ensure that the people who benefit from this climate change adaptation are all the households that live there, particularly the marginal households and women. And the third pillar is the local governance. We believe very strongly that ecology can be best governed by the people who live there. So governance by the local community, in an inclusive committee, including gender and marginalised and ensuring that everybody benefits from this.

At its core, the EbA approach recognises that people need nature – not as something to be used, but something that needs to thrive to ensure their own survival.

AK: If we look at this from the village perspective, the primary stakeholder is dependent on water, good soil for farming, and a healthy ecosystem. If this starts to degrade, it has an impact on their daily lives.

The further we move away from the ground, the more we start to see these things as separate. Marcella gives the example of a panel she spoke on at UNCCD’s COP16 in Riyadh. This panel highlighted that having three separate global conferences on climate, biodiversity, and land degradation means we end up looking at these issues in isolation. But in reality…

MD: I was asked to talk, what is it from the ground level? At the ground, all these conventions merge. There is no difference between climate change and your land that is degraded and managing water and people at the center and strengthening the biodiversity. They all merged.

And that’s really the heart of the EbA approach. While the terminology may be new, the wisdom of it is age-old, and in desperate need of attention in our modern world. So WOTR is intent on scaling it up.

MD: We have the opportunity currently to work very closely with the Government of Maharashtra, with the support of another donor, you know, the ICC. Hopefully it is going to be signed soon, that Ecosystem-based Adaptation is going to be a part of the State Action Plan for Climate Change Adaptation.

W-CReS and WOTR, supported by the India Climate Collaborative, have been working with the Maharashtra government to help them integrate this kind of ecosystem-first thinking into their decision-making. And, of course, ECOBARI is an avenue to build knowledge sharing and bring more people into this space.

AK: When we were working on watershed development, we were working alone, using our own pedagogies. But in EbA, we have brought together our national and international partners through the ECOBARI platform, which helps us learn from other perspectives.

So all in all, it’s been a long road with a lot of twists and turns along the way. From the early years of watershed work to a new focus on restoring nature, it’s truly been a wild ride.

Thanks for listening to In Our Nature! If you like this episode, please share it far and wide to help us get the word out there. We’re super grateful for your support and your attention.

ECOBARI stands for Ecosystem-based Adaptation for Resilient Incomes. Our collaborative aims to spotlight and enable solutions that build climate resilience and sustainable livelihoods by restoring, protecting, and enhancing nature. It’s a shared initiative of nine founding partners with diverse areas of expertise, including rural development, action research, sustainable finance, nature conservation, and policy engagement. To learn more about ECOBARI, visit our website at www.ecobari.org

Speakers

- Marcella D’Souza, Director of WOTR Centre for Resilience Studies (W-CReS)

- Abhijeet Kavthekar, Regional Manager – Dharashiv at WOTR

- Isha Chawla, Anchor, ECOBARI

Credits

Produced by Isha Chawla

Original score by Anurag Baruah

Sound effects from Freesound.org

Music from Epidemic Sound and Track 06 by Chinmaya Dunster (9:25)

Listen to the series here

Sources

National Bank for Rural Development and Agriculture, 2014. Climate Change Adaptation for Sustainable Livelihoods: Learnings from pilot project in Maharashtra. A joint report by NABARD, SDC, and WOTR.

Thomas, R., Davies, J., King, C., Kruse, J., Schauer, M., Bisom, N., Tsegai, D., Madani, K., 2024. Economics of Drought: Investing in Nature-Based Solutions for Drought Resilience – Proaction Pays. A joint report by UNCCD, ELD Initiative and UNU-INWEH, Bonn, Germany; Toronto, Canada.

Jathar, G. et al., 2016. Making Biodiversity A Community Resource: The People’s Biodiversity Register: A “How-To” Manual. A joint report by Watershed Organisation Trust and Maharashtra State Biodiversity Board.

WOTR Centre for Resilience Studies, 2024. Securing Water in a Time of Climate Change through Natural Ecosystems Management. WOTR.