Sanika Diwanji

Team Lead, ECOBARI

India’s climate is no longer shifting along a single axis. It is becoming hotter, drier in some places, wetter in others, and increasingly erratic everywhere. Heatwaves arrive earlier and last longer. Rainfall gets compressed into fewer, more intense events. Dry spells stretch unpredictably between downpours. For millions of people whose lives and livelihoods are tied closely to land, water, and outdoor work, this variability is no longer an abstract climate signal but a daily source of risk. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has confirmed that 2025 was one of the three warmest years on record, continuing a streak of extraordinary global temperatures. This was not an anomaly, but part of a clear and accelerating trend.

As temperatures rise, rains falter, and climate variability loops through extremes, the question is no longer whether India will suffer climate stress, but whether its landscapes, cities, and vast rural hinterlands retain the capacity to buffer climatic shocks. That buffering capacity, the ability of land to absorb heat, regulate water, stabilise soils, and sustain livelihoods under stress, is being steadily eroded.

In response, one solution dominates public discourse and policy messaging alike: plant more trees. The idea feels intuitive and reassuring. Trees provide shade, cool the air, store carbon, and anchor soils. They appear to offer a simple and visible response to an otherwise overwhelming problem. Yet this instinct, while not wrong, is deeply incomplete. In a changing climate, the central challenge is not the absence of tree planting, but the absence of ecological thinking about what trees do, where they belong, and how they function as part of wider ecosystems.

Climate impacts in India are often discussed in fragmented ways, as a heat problem, a drought or deluge problem, an emissions question, a population issue, or a temporary cost of development. Each framing captures part of the truth, but none fully explain why climate stress is intensifying so unevenly across regions and communities. What is increasingly clear is that climatic extremes are being amplified at the scale of land and cities. The loss of tree cover, sealing of soils under concrete, depletion of groundwater, and destruction of wetlands have reduced the land’s ability to regulate temperature, absorb rainfall, and retain moisture.

The consequences are visible across multiple climate risks. Heat stress intensifies where shade disappears and soils dry out. Flooding worsens where vegetation no longer slows runoff. Droughts bite harder where recharge systems fail. In this sense, climate vulnerability in India is as much a land-use and ecosystem problem as it is a global climate one.

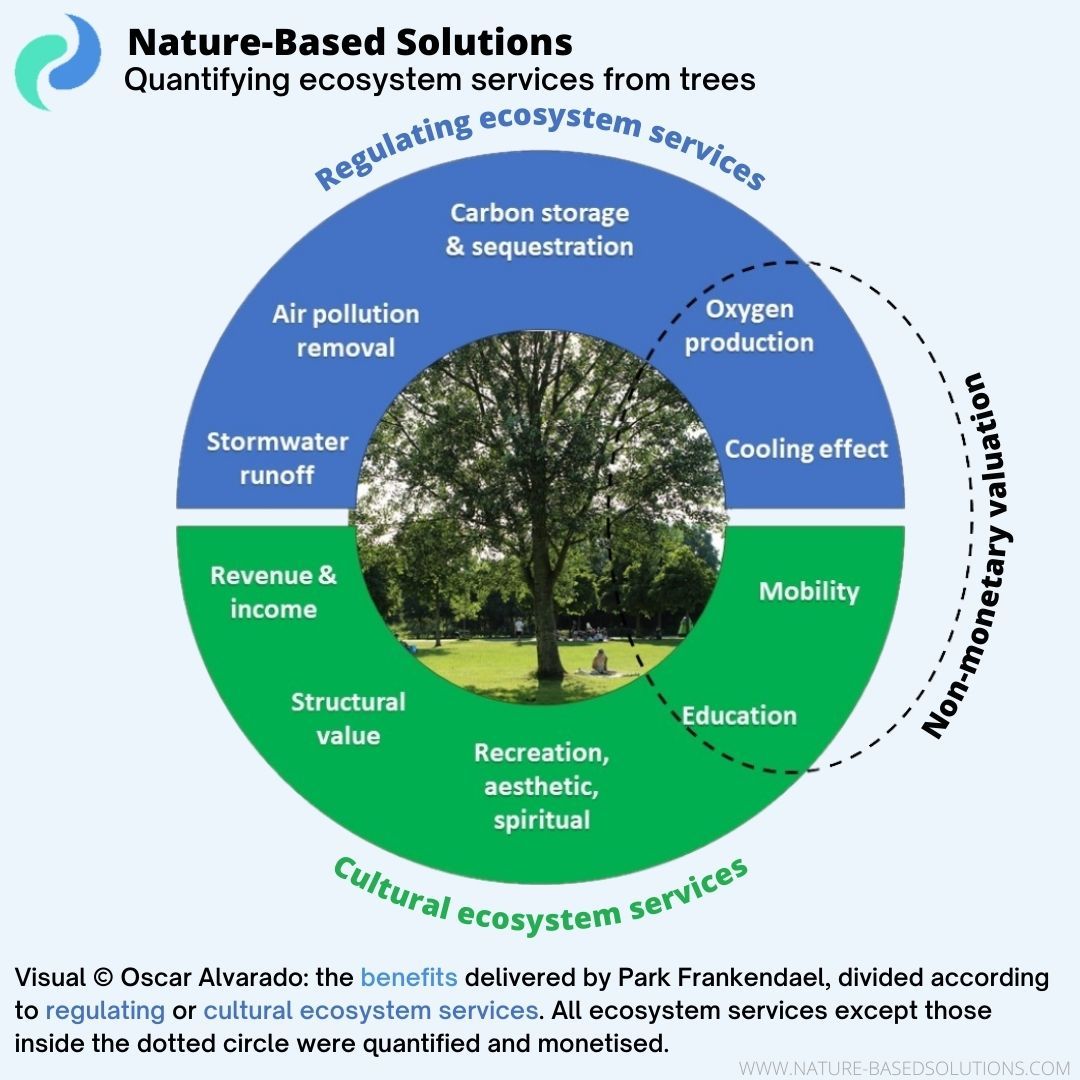

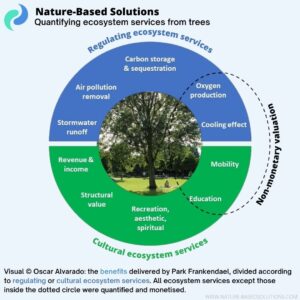

Beyond Numbers: Trees as Ecosystem Infrastructure

Trees matter here not as symbols of environmental concern, but as ecosystem infrastructure. Their role in a changing climate extends well beyond cooling alone. Through shade and evapotranspiration, trees moderate extreme heat. Through their roots and leaf litter, they improve soil structure, reduce erosion, and enhance water infiltration. By slowing runoff and supporting groundwater recharge, they help landscapes cope with intense rainfall as well as prolonged dry spells. For millions of rural and forest-dependent households, trees also provide food, fodder, fuel, and income, acting as livelihood buffers when climate shocks disrupt agriculture and allied activities.

These “ecosystem services” are neither incidental nor easily replaced. They determine whether climatic variability becomes manageable stress or cascading crisis. Large, mature trees with wide canopies and access to moisture deliver these services most effectively, especially in streets, farms, commons, markets, and settlements where people are most exposed.

According to the India State of Forest Report (ISFR) 2023, forest and tree cover together account for 25.17 percent of India’s geographical area. Importantly, much of the recent increase has come from tree cover outside recorded forest areas, rather than expansion of dense natural forests. From a climate resilience perspective, this distinction matters, because ecosystem services such as moisture regulation, soil protection, biodiversity support, and microclimate buffering depend far more on sustained canopy and ecological integrity than on dispersed or short-lived plantations.

At the global scale, India’s reporting to the Global Forest Resources Assessment (GFRA) 2025 places it ninth worldwide in total forest area and third in net annual forest gain. India’s forests are also estimated to remove around 150 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year during 2021 to 2025, ranking the country among the top global carbon sinks.

These are bold claims, and they look encouraging on paper. However, ISFR also highlights that very dense forests, the category most critical for delivering sustained ecosystem services, have continued to decline or remain stagnant, even as overall tree cover has increased. Much of the recent gain therefore comes from trees outside recorded forests and plantations rather than expansion of dense natural forests. From a climate resilience perspective, this distinction is critical, because ecosystem services such as cooling, moisture regulation, and soil stability are driven primarily by sustained, mature canopy rather than by dispersed saplings or young plantations that may take years, if not decades, to begin delivering comparable ecological functions.

Yet public policy, corporate afforestation programmes, carbon credit mechanisms, and popular imagination often treat all trees as interchangeable units. Plantation targets, offset metrics, and compensatory afforestation schemes prioritise numbers planted over ecological outcomes. Multiple audit reports have highlighted persistent weaknesses, from inappropriate site selection and poor survival rates to weak monitoring and community exclusion. The result is a growing gap between what is counted on paper and what actually strengthens ecosystems on the ground.

Not all trees provide ecosystem services equally

A mature native tree with deep roots and space to grow is fundamentally different from a sapling planted in compacted soil, surrounded by concrete, and deprived of water. One reshapes microclimates, stabilises soils, and regulates water flows. The other often becomes a statistic and is forgotten after counting is complete.

Nowhere is this gap more visible than in Indian cities. Large avenue trees are routinely felled for road widening, metro construction, or real estate development, with compensatory plantation promised elsewhere. On paper, the balance appears neutral. On the ground, the consequences are immediate. A forty-year-old tree shading a pavement or bus stop provides instant thermal relief, reduces runoff during heavy rain, and anchors urban soils. Its replacement, a young sapling planted kilometres away or confined to a narrow pit, may take decades to offer comparable benefits, if it survives at all. Meanwhile, street temperatures rise, flooding intensifies during monsoons, outdoor workers face greater exposure, and demand for mechanical cooling increases. From an adaptation standpoint, this is a losing exchange.

The problem extends beyond cities. In rural and peri-urban landscapes, plantation-driven approaches have also struggled to deliver resilience. India has invested heavily in afforestation, including compensatory mechanisms linked to forest diversion. Multiple audit reports have pointed to persistent weaknesses such as inappropriate site selection, inadequate soil preparation, poor maintenance, delayed use of funds, and survival rates that fall well below targets. The issue is not a lack of effort, but a mismatch between ecological complexity and administrative design. Plantations prioritise speed, scale, and visibility, while ecosystems require patience, care, and local knowledge.

In some regions, the issue is more fundamental. India’s landscapes are diverse. Grasslands, deserts, and alpine systems are not degraded forests waiting to be planted. Treating them as such can damage native biodiversity, alter hydrology, and undermine livelihoods tied to open ecosystems. For pastoral and forest-dependent communities in semi-arid and grassland regions, plantation drives have at times reduced access to commons without delivering commensurate ecological benefits. The assumption that more trees are always better obscures the fact that the right response depends on the land itself.

This is particularly evident in semi-arid regions where climate change manifests through rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, and groundwater decline. Where tree cover along field boundaries, commons, and drainage lines has been lost, soils degrade, water retention weakens, and crops become more vulnerable to both droughts and intense rainfall. Conversely, landscapes that invest in soil restoration, native tree regeneration, and water harvesting tend to withstand climate variability more effectively. The difference lies not in the presence of trees in isolation, but in trees embedded within functioning ecosystems that include healthy soils, recharge pathways, and collective stewardship.

Any discussion of trees in India must also confront livelihoods. Estimates suggest that roughly 275 to 300 million Indians depend on forests and tree-based systems for at least part of their income, food, fuel, or cultural life. For these communities, trees are not climate abstractions. They are assets and often safety nets. When managed as part of functioning ecosystems, trees support diversified incomes, soil fertility, water availability, and resilience to climate variability. When reduced solely to carbon sinks or canopy metrics, they risk marginalising those who have sustained these landscapes for generations.

These tensions are sharpened by ongoing debates around forest governance and land classification. Changes in forest legislation and their interpretation have raised concerns about what land is protected, what is diverted, and who decides. While the legal details are complex, the underlying lesson is simple. Trees cannot be separated from land, institutions, and people. Adaptation strategies that ignore this reality may achieve short-term targets but struggle to sustain long-term outcomes.

What, then, does a credible tree strategy look like in a rapidly changing climate?

It begins by shifting the starting question. Instead of asking how many trees can be planted, it asks whether tree interventions are reducing vulnerability to climate extremes, whether they are surviving the rising temperatures and water stress, whether soils and water systems are being restored alongside canopy, and whether livelihoods and local governance are being strengthened rather than displaced.

This is the shift ECOBARI argues for, from tree planting as an event to trees as part of living ecosystems.

To make this shift practical rather than abstract, ECOBARI frames tree and landscape interventions through a simple but rigorous lens referred to as the 5R approach. This framework is not a checklist for planting drives. It is a way of asking better questions before decisions are made.

Right Purpose

Why are trees being introduced here in the first place? Is the objective cooling, water regulation, biodiversity support, livelihood security, or a combination of these?

Right Place

Does this landscape ecologically support tree cover, or does it function better as a grassland, wetland, or open system?

Right Species

Are the species native or locally adapted? Can they survive rising heat, variable rainfall, and local soil conditions?

Right Time

Are climatic conditions, soil moisture, and land-use context suitable for planting or regeneration at this moment?

Right Approach

Who will protect, maintain, and benefit from these trees over the long term?

Taken together, these questions move the conversation away from counting saplings and toward building resilience. They allow tree strategies to be evaluated not by scale alone, but by their contribution to ecosystem health, climate buffering, and livelihoods.

In a climate-vulnerable India, trees remain one of the most powerful tools available to us. But they are not a shortcut. They demand protection of what already exists, investment in soils and water systems, and governance that recognises land as living space rather than empty terrain.

Over the next articles in this series, ECOBARI will explore each element of the 5R approach in depth, grounding it in Indian landscapes, institutions, and lived realities. Trees can help. But more importantly, when embedded in healthy ecosystems, they help societies adapt to a climate defined by uncertainty, extremes, and inequality. Getting the reason, place, species, timing, and approach right is not about planting more trees. It is about rebuilding the ecological foundations of resilience.

References

India Meteorological Department (IMD), Annual Climate Summary 2024

India’s warmest year on record since 1901 with the 2024 annual mean land surface temperature +0.65°C above the 1991–2020 average.

https://internal.imd.gov.in/press_release/20250115_pr_3554.pdf

National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), Guidelines for Preparation of Action Plan – Prevention and Management of Heat-Wave

Official national guidance on managing heat impacts and Heat Action Plans.

https://www.ndma.gov.in/Natural-Hazards/Heat-Wave

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Advisory for State Health Departments on Heat-Wave Season 2024 (NPCCHH)

Health system advisories for tracking heat-related illness and heatstroke.

https://ncdc.mohfw.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Advisory-for-State-Health-Department-on-heat-wave-season-2024_NPCCHH.pdf

Forest Survey of India (FSI), India State of Forest Report 2023 (ISFR 2023)

Forest and tree cover data (total, forest cover, tree cover, and trends).

https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2086742

Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG), Performance Audit on Compensatory Afforestation in India

Audit documentation on plantation survival, site suitability, monitoring, and utilisation gaps.

https://cag.gov.in/webroot/uploads/download_audit_report/2024/Report-No.-5-of-2024_PA-on-CAMPA_UK_English.pdf

Press Information Bureau (PIB), Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India. Press Release on Forest and Tree Cover in India. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2182269®=3&lang=2

World Bank Group, India: Forests for Prosperity

Assessment estimating roughly 275 million people depend on forests for at least part of their livelihoods.

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/4959ffbd-48b7-5c44-a1ea-4cbc3d5db669

Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC)

Parliamentary responses citing ~300 million forest-dependent people and ~170,000 forest-fringe villages.

https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/1714/AU2405.pdf

Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act, 2023

Recent amendments affecting forest land classifications and protections. https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A2023-20.pdf

Supreme Court of India Orders on Forest Conservation Cases. Example order on forest law interpretation and applicability.https://main.sci.gov.in/pdf/SupremeCourtReport/2024_v1_piv206.pdf

Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR). Connecting the Dots: Why Ecological Connectivity Is Central to Land Restoration and Resilience.

https://wotr.org/blog/connecting-the-dots-why-ecological-connectivity-is-central-to-land-restoration-and-resilience/

Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR) and WOTR Center for Resilient Studies (W-CReS). Rising Land Surface Temperature and Its Implications. https://wotr.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Rising-Land-Surface-Temperature-and-its-Implications.pdf

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), AR6 WGII: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability

International synthesis on heat impacts, adaptation options, and vegetation roles. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2

Further Reading

Ecosystem-Based Adaptation (EbA) for Everyone

UN Environment Programme easy guide to EbA principles and community benefits.

https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/ecosystems-and-biodiversity/what-we-do/ecosystem-based-adaptation

Understanding Heat and You

“Heat Waves and Human Health” World Health Organization explains what heatwaves are and how they affect bodies and communities. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/heatwaves

Urban Heat Islands Simplified

National Geographic video and explainer on why cities get hotter and how vegetation helps.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/urban-heat-islands

Tree Benefits Explained

US Forest Service guide on how trees cool cities, manage water, and improve well-being.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/ccrc/topics/urban-forestry

Soil and Water Basics

Soil Science Society of America overview of soil health and its role in climate adaptation.

https://www.soils.org/discover-soils/why-soils-matter

To cite this article, please copy:

Diwanji, S. (2026, February 9). India’s Climate Challenge: Focusing on Ecosystem Health, Not Just Tree Counts. ECOBARI. https://ecobari.org/indias-climate-challenge-focusing-on-ecosystem-health-not-just-tree-counts/.